John Ware, Canada’s Legendary Cowboy (1845-1905)

Free post. This Article is dedicated to Nettie Ware (1893-1989)

Note: A previous version of this article was provided to Oxford University Press Canada for use in their Canadian high school textbook Inside Track 1.

“A man of unquestioned honesty and agreeable nature…[who] boasted the rare distinction of never having been thrown from a horse. At roughriding and roping he was an expert’ (Turner, 1950, pg. 461).

Sometimes in life you are in the right place and the right time to meet the most amazing people.

When I lived in Calgary, Alberta during the late 1970s, I stayed in a boarding house run by a kind elderly lady. Often, I would spend many afternoons in my landlady’s kitchen chatting to her best friend Miss Janet “Nettie” Ware. My landlady and Nettie were longtime friends from when they were both teachers in the small town of Vulcan, Alberta.

Often Nettie would talk about her father John Ware.

At the time I had no idea who John Ware was but after some prompting from my landlady, Nettie was happy to share her stories about her father, who as it turned out was one of the most famous of Canadian cowboys.

Learning about John Ware from Nettie Ware

Many books and videos have been made about John Ware, but this is the story about how I came to learn about John Ware.

The Blackfoot Indians called him “Matoxy Sex Apee Quin” because they thought John Ware was related to the spirit world. He was undoubtedly one of the best cowboys ever to ride on the prairies during 19th century Canada. But to me, what makes his story more amazing than his skills, which were extraordinary, was his backstory.

He was a freed slave who made western Canada his home and through his reputation became a hero to many black Canadians.

John Ware was a cowboy who lived in the latter decades of the nineteen century in Alberta, Canada. He was not some Hollywood-style imaginary gun-slinging desperado. He was a professional, business-like cowboy who was highly respected amongst his peers not only because of his skills as a cattle hand but also because of his character and deportment.

What made John Ware unique amongst the many cowboys of Alberta was his origin story and what he became in his new home of Alberta on the Canadian prairies.

“Go west young man”

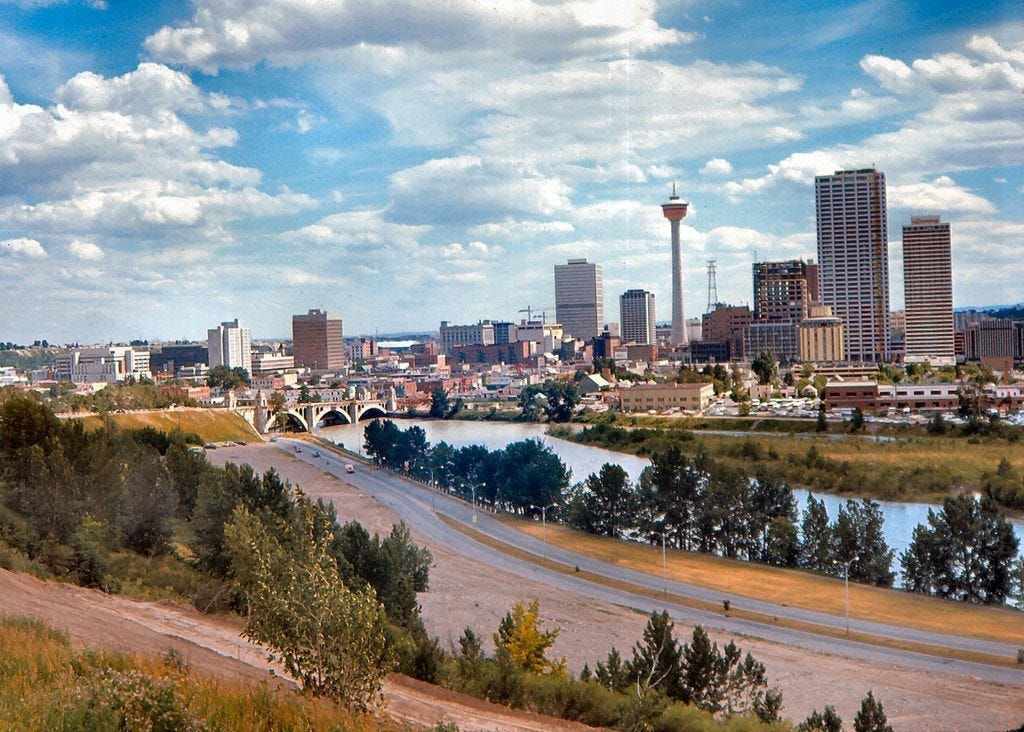

When I was 17-years-old. heard the call to “Go West Young Man”. Back in the 1970s many young people made the journey from eastern Canada to the Oil-Rich province of Alberta. Well, the truth is, this call was more a request from my friend to drive him back home to Calgary, Alberta. And so, I did. I had no idea where Calgary was except it was in Western Canada.

As we drove across the prairies towards Calgary, I was astonished at the vastness and sheer magnificence that is Canada.

Calgary during the 1970s was at the height of the province’s boom years. The city was thriving. Everything was possible. Living there was like magic to me. Although Ontario has mountains, I had never seen mountains as high as the Rockies just to the west of Calgary. And I had never seen a sky as blue and never-ending as I saw in Alberta. For good reason the province is called Big Sky Country.

Those were formative years for me as I moved from suburban Toronto as a teenager to the “Wild West” of Calgary. Well, it was not particularly wild, but it was new and wonderful to me.

After settling into life there, I decided to learn mountain climbing and spend some time hiking in the wilderness.

One day I decided to climb a mountain called Mount Lady MacDonald which was easy to access as it was near Cranmore, Alberta.

Climbing the mountain was exhilarating, adventurous and challenging. That was until I discovered I had forgotten to bring a flask of water with me. Having managed to find some snow behind some bushes, I hydrated myself. But snow is not a good substitute for water.

After reaching the summit and taking a few photos, I got myself down the mountain as fast as I could. Using my boots as brakes I made it to the base of the mountain in less than a half hour. I then ran towards the townsite of Cranmore (which was across a four-lane highway) hoping to find a water source. I stumbled upon a church and finding an outdoor tap in the back of the building, I drank as much as I could.

But I digress. This is not the point of this article, but it is a fun story.

Meeting Miss Janet “Nettie” Ware

I quite enjoyed chatting with my landlady. Once a week her best friend Janet Amanda “Nettie” Ware visited and my landlady invited me to join them for tea. They were happy to share stories about the early days of Alberta.

And what a past they had!

It is through them, especially Nettie, that I learned about a famous cowboy named John Ware. I’ll share what I learned shortly.

After three years living in Calgary, I moved to the United States to attend university, oddly in the entirely opposite direction that John Ware travelled more than one hundred years previously.

However, life moved on and I slowly forgot about this episode in my life as I got busy with new things in Pennsylvania and New England.

A few years later I moved back to Canada to attend a university in Ontario. After studying Canadian literature, especially from Western Canada, it occurred to me that I remembered my time in Calgary, especially meeting Nettie Ware. I wondered if she was still alive and what she might be doing. I had no means of contacting her, so I checked the newspapers and obituaries.

Initially, I did not get far. Later, while doing some more in-depth research, I was saddened to learn that Nettie Ware had passed away in 1989 on her ninety-sixth birthday. This meant she would have been in her mid-eighties when I had chatted with her at the rooming house in Calgary. She had given me a signed copy of a book written about her father John Ware. After searching amongst my books, I discovered I had lost it. (I hope it found its way to a used bookstore somewhere).

Who was John Ware?

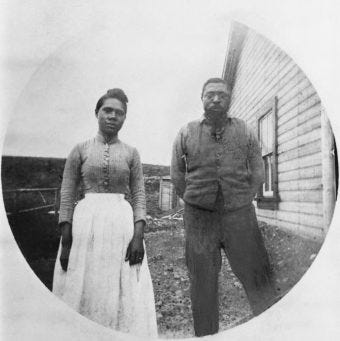

Sometime during 1845 in North Carolina (South Carolina? historians are uncertain of where he was born), John Ware was born into slavery. This was sixteen years before the American Civil War that brought liberty to him and thousands of other slaves.

Upon liberation, he was quick to leave the places that had enslaved him. Slaves were treated as commodities to be bought and sold and John wanted nothing to do with those states who allowed this. The degradation of African Americans under slavery remains as a stain on the history of the United States. Nothing can repair the stolen lives of millions of humans whose sole purpose was to generate income for slave owners in the American south. John Ware was born expecting to become another cog in that wheel of injustice.

The emancipation of slaves that followed the North’s victory in the Civil War gave John Ware the opportunity to find his own way in life. Somehow, he found his way to Texas and became a cattle hand (a “cowboy”). At over six feet tall and weighing 230 lbs., he took to his tasks easily and became very proficient at handling great herds of cattle.

A cowboy’s work is never done

His work as a cowboy was extremely difficult. Working conditions were hard and if he were injured or disabled, he could not expect much in the way of assistance, except through the kindness of his neighbours or friends.

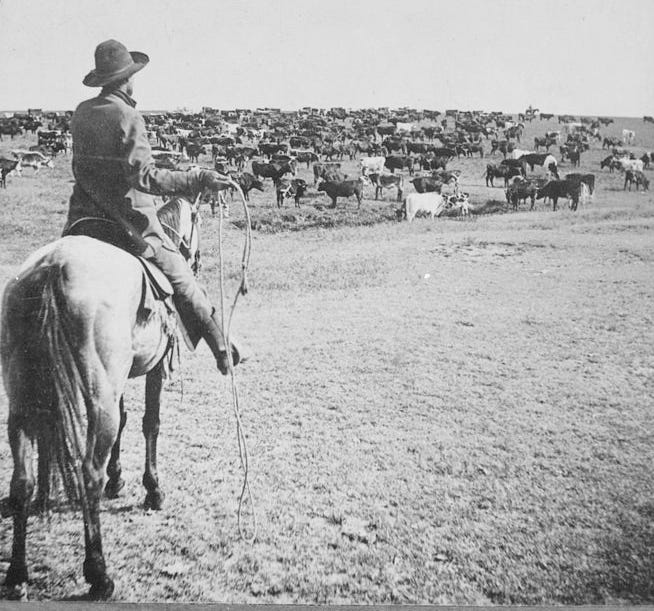

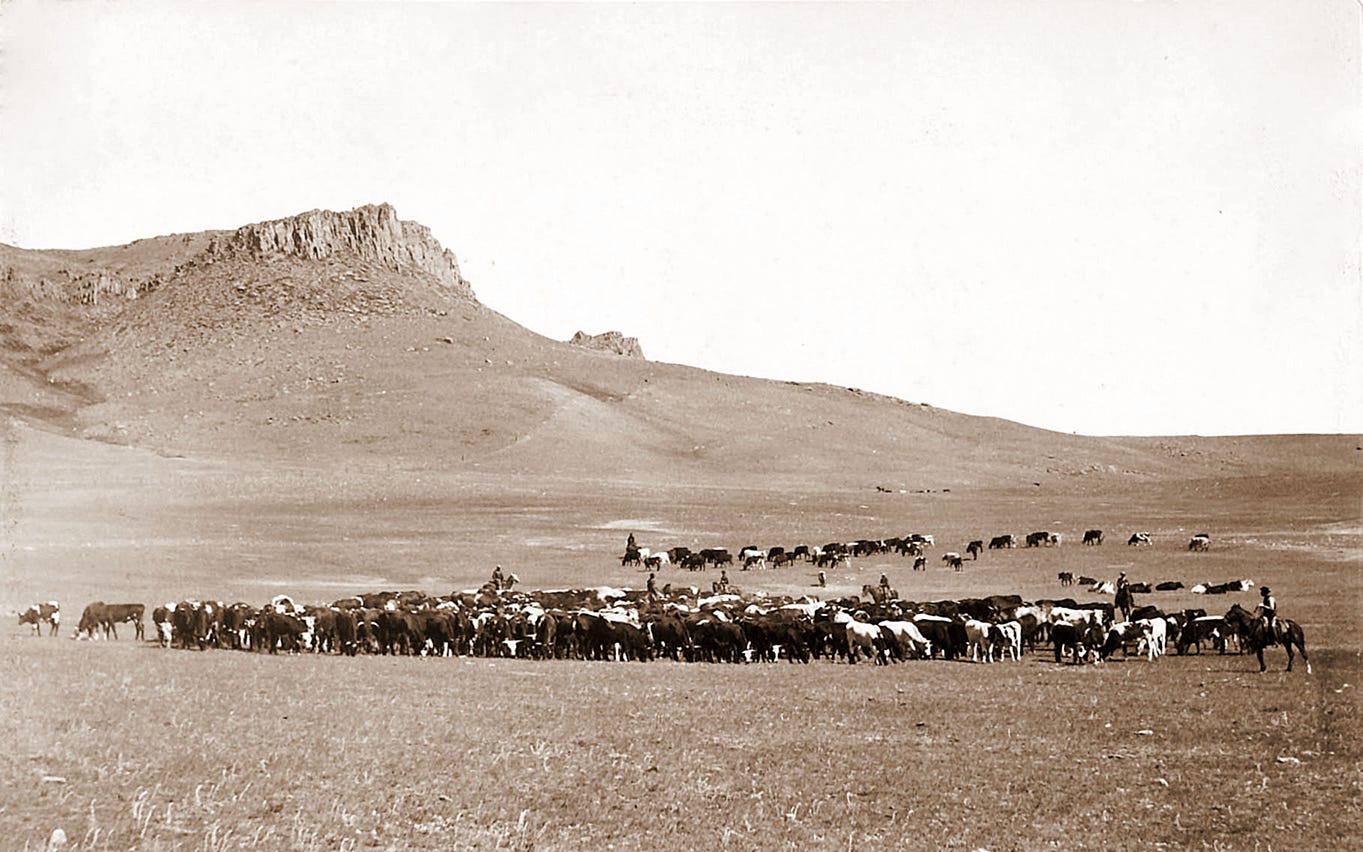

What was the work of a cowboy? They were primarily responsible for the well-being of the cattle under their care. They were also responsible for moving herds from sellers to buyers at other ranches. In all cases they needed to ensure the herd was well fed (had grazing land) and protected from predators and/or cattle rustlers.

When the herd had to be moved to new pastureland for better feeding, cowboys needed to know how to get the herd moving in the right direction. In the days when fences were unheard of in the western plains, they also had to keep cattle from wandering away from the main herd.

Nettie Ware shared with me some lesser-known facts about a cowboy’s life.

For instance, part of a cowboy’s job during a cattle drive was to ensure the cattle did not stray off or turn back. The herd of cattle is continually running driven on by the cowboys. The herd could have numbered in the hundreds of head of cattle. To keep the cattle going the right direction, the lead cattle must head in the direction the cattlemen wanted them to go. It was not like herding cats, but in a wide-open land it was not an easy task. One tactic was to fire a shot just in front of the lead cattle to make them turn, while being careful not to injure them. If that did not work, the cowboy had to take his horse and gallop in front of the herd and force them to turn using the horse - an extremely dangerous and life-threatening tactic if the cattle did not behave.

This was the life of a cattle hand. It required stamina, strength and courage and an ability to quickly make tough decisions.

From Texas to Alberta, Canada

John Ware often went on cattle drives to move a set number of cattle to the purchasers on distant ranches. For example, ranchers on the northern plains bought hundreds of head of cattle from suppliers in Texas. Before the arrival of trains, Texas Longhorns were the type of cattle that could survive the long drives through arid land and western prairies.

In 1882 at the age of thirty-seven he joined a cattle drive delivering a herd to a buyer in Idaho. After arriving in Idaho, he then joined another drive that was bringing a herd of cattle across the border to a buyer in Alberta.

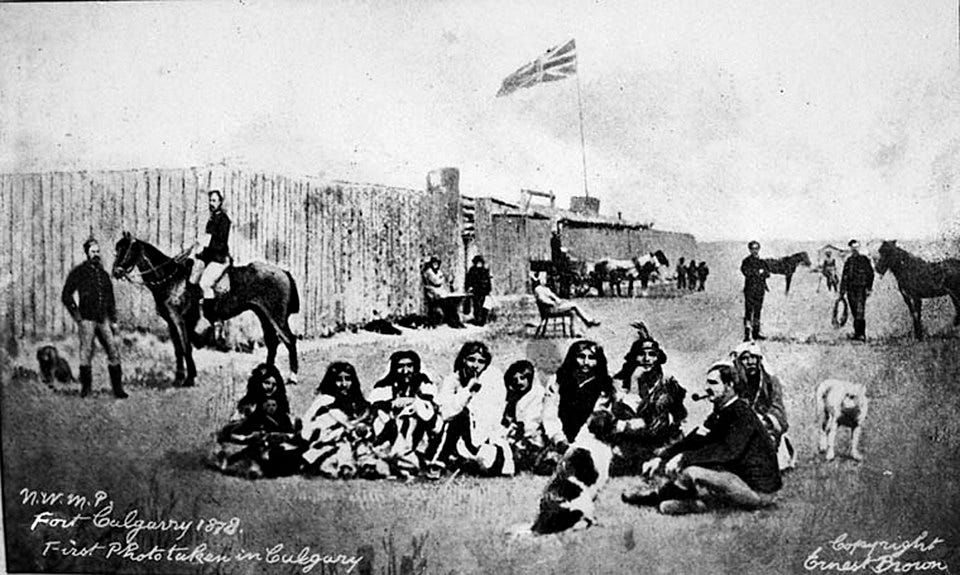

After driving the cattle into the Canadian territory of Alberta, he delivered the herd to the buyer. Released of his work, he then went to the dusty cattle town of Calgary, Alberta. Having looked at the place, the people and the opportunities, he decided to settle in there.

This seemed like a good move as this territory was opening for settlement. The North-West Mounted Police (later called the RCMP) had established “law and order” in the territory. These mounted police were formed to protect the First Indigenous tribes from unscrupulous whiskey sellers, especially American whiskey traders who would sell tampered alcohol to the Blackfoot tribes, as well as other tribes on the prairies.

With good relations between the white settlers and the tribes (for the most part), John Ware faced less racial discrimination there than he would have experienced in the American south.

Alberta was his new home.

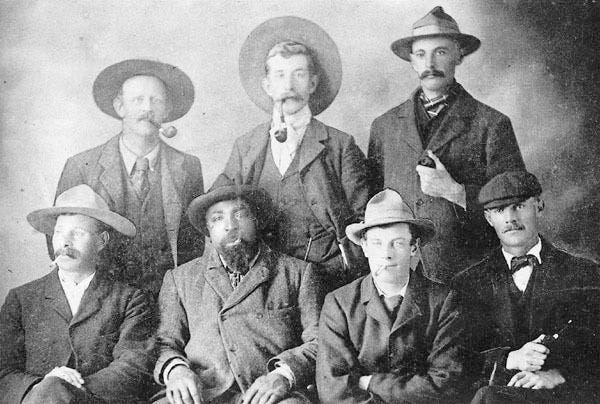

John Ware’s reputation

He quickly found steady employment at the Bar-U and Quorn ranches south of Calgary. They were in an area north of what is today called Lethbridge.

In the late 19th Century, cowboys had a reputation of being tough, rough and at best dishonest, John Ware stood out as being the exception. Turner, describing John, wrote the following:

“A man of unquestioned honesty and agreeable nature…[who] boasted the rare distinction of never having been thrown from a horse. At roughriding and roping he was an expert” (Turner, 1950, pg. 461).

This made him a valuable employee of the ranches where he worked. His fellow ranch hands respected him for his abilities and his honesty.

His skills at bronco busting were legendary. Bronco busting is not for the faint-hearted. It is a bone jarring activity and was a vital part of ranching in those day. A steer needed to be captured and held so it could be “labelled” by a ranch’s “brand” which was burnt into the hide of the animal near its business end. This brand ensured the owner of the animal could be clearly identified if it were rustled or stolen. Most significantly, the brand could not be taken off without killing the animal. Bar-U and Quorn ranches had their own unique identifier brands which cowboys were expected to burn into the hide of the animals.

In an era when the demanding skills of a cowboy were highly valued in Alberta, John Ware’s skills exceeded them all. When he entered an establishment in Calgary, everyone knew him.

The legend of John Ware

Now, legends being legends, many of yarns have been made turning John Ware into a giant like Paul Bunyan. These legends included:

John Ware discovered the Turner Valley oil fields with a flick of a match

John Ware was the last rancher to use a Calgary bridge as a cattle crossing

John Ware was never thrown from a horse

He invented steer wrestling 20 years before the Calgary Stampede

Camp cooks profess to feeding him on over-sized platters and to watch him eat sandwiches the size of a family bible

How much of these legends are true, well, you decide. It is quite possible that they are all true.

Nevertheless, it is true he was the last to use a Calgary bridge as a cattle crossing. It was forbidden to drive cattle through Calgary - a perfectly reasonable law - except when your new ranch is on the opposite side of Calgary from your old ranch. That was exactly John Ware’s problem. He had bought a new ranch but had to get his herd there. But Calgary was in the way. What to do? He brought his herd to the edge of the Bow River and waited until nightfall. In the middle of the night, he charged his cattle across the bridge and into history.

He was the last rancher to use a Calgary bridge as a cattle crossing.

The legacy of John Ware

I should mention that Nettie Ware did not speak much about his father’s life as a cowboy except what I mentioned here. She mostly spoke about John Ware as her father.

Nettie Ware told me he was a good man and a good father. He had raised his children to be honest and taught them to respect one another and to “treat one another as they would like to be treated.” Certainly, based on my memories of Nettie, John Ware had done an excellent job of raising his children.

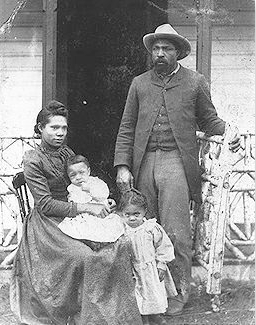

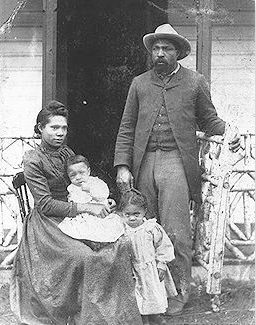

In 1890 John Ware bought property near a stream which today is called Ware Creek near the village of Millarville southwest of Calgary.

In 1892, John met a woman from Toronto named Mildred Lewis (I knew there was an Ontario connection somewhere). They married and in 1900 settled on a ranch east of the village of Duchess, Albert. This was about 200 km from his original land which indicates he expected his herd of cattle to increase significantly.

John built a cabin near the banks of the Red Deer River by retrieving logs floating down the river. Unfortunately, two years later in 1902 spring floods washed his cabin away. By then John and Mildred had five children.

John Ware rebuilt the cabin on higher ground overlooking the river.

Three years later in 1905 Mildred Ware died of pneumonia. Tragically, that same year John Ware died when his horse tripped after stepping into a gopher hole. The horn of the saddle killed John instantly. Nettie and her siblings were bereaved of both of their parents in the same year. Nettie was only 12 years old when both her mother and father passed away.

I cannot recall what Nettie said had happened to her and her siblings after her parents died. John Ware’s children would certainly have been taken care of as he had provided good service to many others.

However, I do know that when Nettie was older, she settled in Vulcan, Alberta and became a teacher.

It was during her time in Vulcan that she got to know my landlady as a fellow teacher. My landlady eventually moved to Calgary after her retirement to start a rooming house for students at a nearby college. Nettie, however, remained in Vulcan, Alberta and frequently visited my landlady.

Hero to Canadians of African origin

John Ware was indeed a legendary cowboy, a skilled bronco buster and most importantly a gentleman and good family man.

John Ware died 12 days after Alberta entered confederation within the new nation of Canada. And it does seem fitting. From slavery to freedom in a new country. John was a decent man. He was highly respected and an extraordinarily talented - even legendary - cowboy. And he was black.

In time he became a symbol of tolerance and decency. And he became a hero to Canadians of African origin.

Eventually, Nettie Ware began traveling throughout Alberta speaking about her father to schoolchildren. In 1971 the Province of Alberta honoured her with “Alberta’s Pioneer Daughter of the Year”. Nettie kindly gave me a book about the history of John Ware, and she even signed it for me. Somehow, frustratingly, I lost it in my travels. (Update: I managed to find another copy, and it sits proudly in my bookcase of Canadian classics.)

As mentioned, I lost contact with both Nettie Ware and my former landlady, but I have often told my story about meeting Nettie Ware and learning about this great Canadian cowboy.

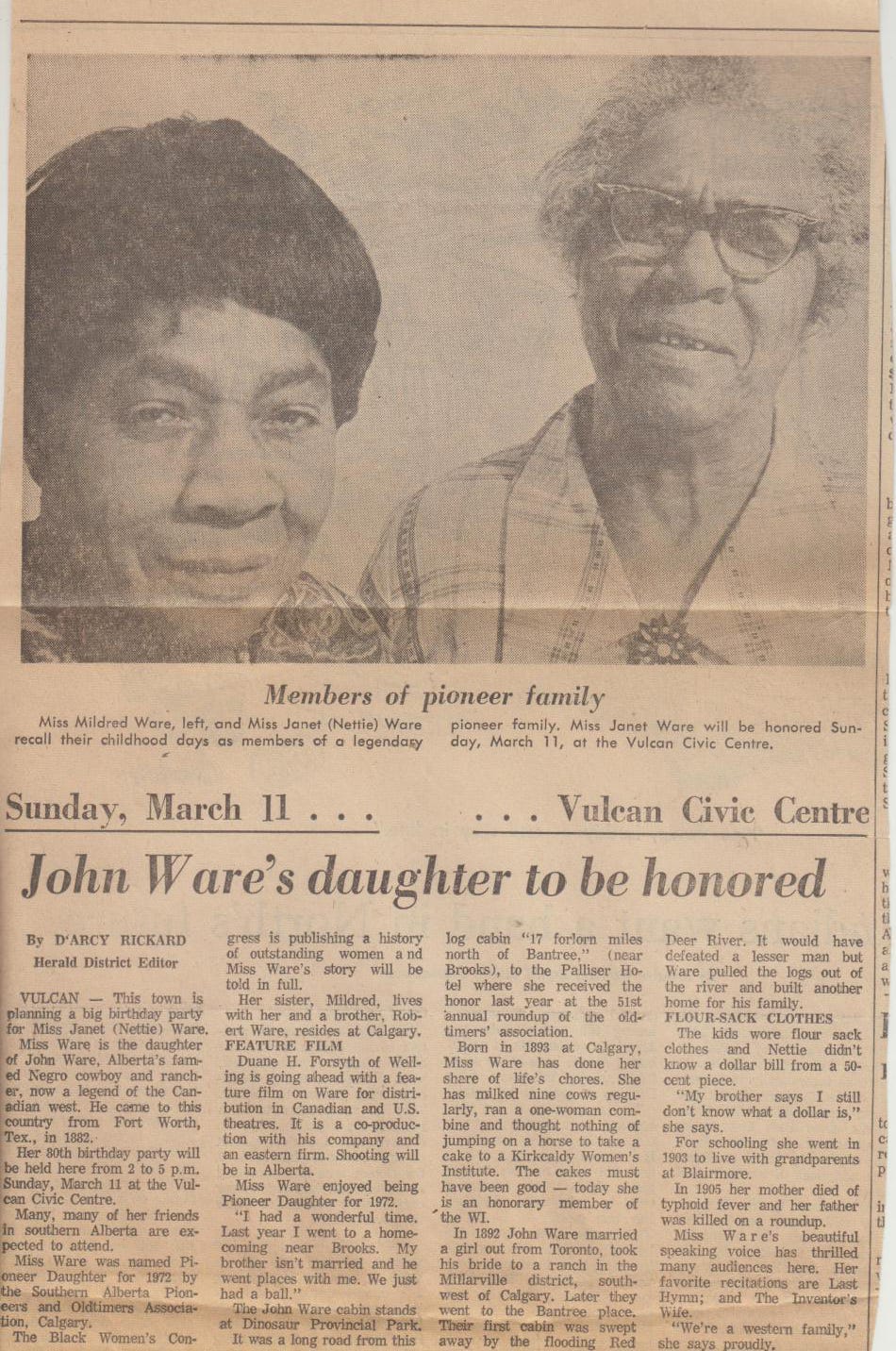

This story would not be complete without showing this small memorial to Janet Amanda “Nettie” Ware. She rests in peace next to her sister Mildred in Vulcan, Alberta.

An important (coincidental) connection with Nettie Ware: She died in 1989, which was the year I began my studies at the University in Waterloo in Ontario. The year I first met her was 1978. That was the year I began an adult education program in Calgary to finish my high school which would later allow me to enter University.

Epilogue

The story of John Ware is an important story to keep alive. It is part of the heritage of Canada. Canadians of African descent can be rightly proud of John Ware, as can all Canadians.

From Canada’s founding in 1876, despite some serious mistakes along the way, Canada has striven to be a home for all people, no matter their colour or nationality. For John Ware, Canada represented freedom - a freedom from racism and intolerance. And Alberta has been proud of one of its own who showed others what decency and honesty and hard work is all about.

Further Reading

Here are some online resources for further reading. Googling John Ware will retrieve lots of information on John Ware.

Books about John Ware

John Ware’s Cow Country by Grant MacEwan. Book written by Alberta’s former Lieutenant Governor of Alberta. This is the one that I lost (with Nettie’s signature!).

The Story of John Ware by R. Breon, V. Cudjoe, M. McLoughlin (Illustrator) Children’s illustrated book about our famous cowboy.